Ritorno nel Ghastengarda

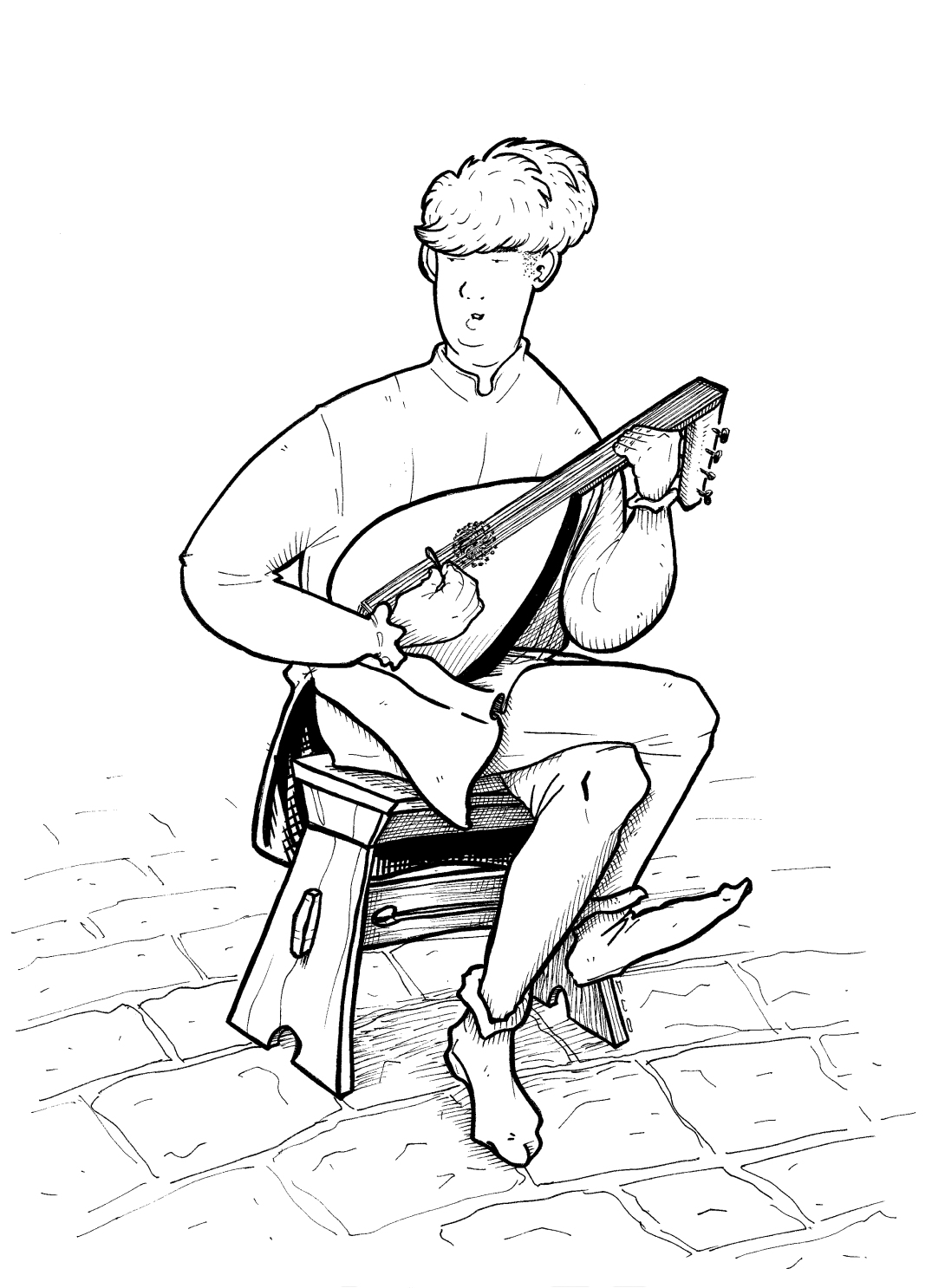

Illustrazioni di Francesca Duo

“Ah, che nostalgia!” disse papà, stranamente allegro, quando partimmo la mattina seguente. “Mi ricorda le mie prime avventure con Quis, al fianco di mio padre, quando avevo la tua età…”.

Passammo di nuovo davanti alla bancarella di frutta secca del generoso Anselmo, che ci salutò caloroso, ma purtroppo papà non si fermò. Presto arrivammo alla stessa viuzza dell’altra volta. Questa volta scoprii un nuovo dettaglio: fu proprio papà a richiamare il corvo spargi-nebbia, con un piccolo rito strano. Prese uno scalpello e con grande cura lo mise orizzontale in equilibrio perfetto su un dito esteso della mano sinistra. Poi, con altrettanta cura, prese il martello e diede quattro colpi leggerissimi alla lama dello scalpello, con un ritmo particolare: ta ta TA ta.

“Ecco,” disse a me e Pietro, “serve farlo tre volte per chiamare Becherta”.

“Chi?”

“Il corvo”.

“Ah”.

“Fai tu il prossimo, Pietro?”

Mio cugino fece cenno di sì. Matteo lo aiutò a mettere lo scalpello in equilibrio sul dito e gli diede il martello.

“Tieni. Lo faccio con te” gli disse. Pietro tenne il martello e Matteo tenne la mano di Pietro dentro la sua mano molto più grande. Insieme, fecero ta ta TA ta.

“Bene,” disse papà, “ora tocca a Faro”.

“Posso farlo da solo, papà? Ce la faccio…” implorai.

“Se non ti viene bene…” papà era incerto, poi mi guardò negli occhi “va bene lo stesso. Provaci”.

“Grazie papà!”

Effettivamente ci misi un sacco di tempo a mettere lo scalpello in equilibrio e poi quando allungai la mano per il martello cadde, e dovetti ricominciare. Povero papà, era impazientissimo, si trattenne e non disse niente, lasciando mi fare. Dopo un po’ lo scalpello era messo bene.

“Bene, ora devi fare i colpi più leggero che puoi, altrimenti fai cadere di nuovo lo scalpello”.

“Va bene, papà”.

Concentratissimo, feci ta ta TA ta.

“Bravissimo!” dissero papà e Matteo insieme.

“Vedi? Te l’ho detto che ce l’avrei fatta…” e gli porsi gli attrezzi.

“Ssst. Non lo senti?”

Restammo tutti in silenzio, e udii un rumore… un battito di ali. Come la prima volta, il corvo nero – Becherta – scese nella viuzza, e si posò su una trave per un attimo.

“Incredibile!” dissi, “ma papà, è così facile? Lo potrebbe fare chiunque. Non sarebbe poi un segreto”.

“Eh, no, Faro, innanzitutto non finisce qui. Ci sono ancora due prove da affrontare prima di entrare nel Ghastengarda. E poi, Becherta non viene per chiunque. Solo un capomastro che fa il ritmo con gli stessi attrezzi che userà per scolpire il racconto può chiamare il corvo del mondo dei racconti”.

Becherta lo guardò con un occhio nero, e mio papà fece un leggerissimo inchino.

“Papà, anche gli altri capomastri sanno del Ghastengarda?”

“Non tutti. Siamo in tre famiglie, ma facciamo i modelli per tutti. Altrimenti, come si potrebbe costruire tutta una basilica ricoperta di figure?”

Salutato mio padre, Becherta dispiegò nuovamente le ali e se ne andò su e giù spargendo nebbia, riempiendo pian piano tutto lo spazio di un grigiore fitto e misterioso. Poi, il corvo se ne volò dentro la nebbia, scomparendo.

Papà guardò severo me e Pietro.

“Ragazzi, c’è una promessa che mi dovete fare prima di entrare nella nebbia”.

Lo guardammo con serietà solenne.

“Dentro il mondo del racconto, dovete solo e soltanto guardare. Non dovete toccare nulla, non dovete fare nulla. Solo guardare. D’accordo?”

Facemmo entrambi un cenno di sì con la testa.

“Allora, seguiamo Becherta!” disse papà.

Come la prima volta, dentro la nebbia ci trovammo in una via diversa, strana, con muri liscissimi e coperti da simboli strani dipinti con colori vivaci. Camminammo un poco senza parlare. Guardavo i simboli e mi chiedevo cosa potessero significare. Papà si fermò davanti a una parete larga, con tanti disegni strani.

“Ecco” disse, “la prima prova. Dobbiamo capire qual è il simbolo giusto. Spiegò a me e Pietro. “Le ultime tre pietre per la facciata rappresenteranno le virtù della Fede, della Speranza e della Carità. L’altro giorno abbiamo visto il racconto della Fede, i pesci. Ci serve ora il racconto della Speranza. Secondo voi, quale immagine sarà? Posandoci sopra la mano, questi disegni aprono portali ai racconti, ma ce ne sono tanti. C’è un vero labirinto di racconti dietro questa parete. Non possiamo sbagliare…”

Matteo venne avanti.

“La spada di certo no, direi” disse, indicando un disegno senza toccare la parete. “Significa tutto tranne la speranza, nella mia esperienza. Ragazzi, voi che dite?”

Guardai tutti i disegni, ma non trovai la Speranza. Era più facile dire quello che non si doveva toccare.

“Nemmeno le monete d’oro, vero papà?”

“Mmmm…direi di no, Faro. Il denaro non è speranza, benché a volte gli sciocchi lo scambiano per essa. Certo, oggi il rebus è difficile. Certamente la speranza non sarà questo leone addormentato…”

“E nemmeno il drago rampante…” aggiunse Matteo.

“Non so, neanche questo pavone che beve da una coppa non mi sembra la Speranza…” feci io.

Fu Pietro che, senza dire una parola, indicò il disegno più piccolo di tutti.

“Cos’è, Pietro?” Fece Matteo.

“Non è un seme, papà? Può essere?”

Lo guardammo tutti. Era un seme.

“Si, si, sono d’accordo con te Pietro” disse papà. “È vero che è una cosa piccola, ma può diventare qualcosa di più grande. Secondo me, questo è il disegno che fa per noi. Matteo?”

“Si, d’accordo. Bravo Pietro.”

Papà mise una mano sulla spalla del piccolo cugino.

“Allora, ci posi la mano tu?”

Pietro mi guardò.

“Fallo tu, Pietro” dissi.

“Sicuro?”

“Certo.”

Posò la mano sopra il disegno e… la parete tutto attorno scomparì, al suo posto un’apertura completamente buia. Ora Pietro guardò mio papà un po’ spaventato.

“Tranquillo,” gli disse papà, “non ti farò entrare per primo. Vado io avanti, tuo padre per ultimo, va bene? Così voi ragazzi siete in mezzo, e non perdiamo nessuno.”

Dentro il buio per qualche tempo ancora non vedemmo niente. Andammo avanti a passo lento, con papà che ci incoraggiava.

“Forza, sempre avanti piano, vediamo quale scherzo ci fa Quis oggi. C’è ancora una prova.”

Presto però quel buio pesto cominciò a schiarirsi e andavamo verso una luce proprio come quella della viuzza di prima. Anzi, emergemmo proprio nella viuzza di prima, sempre piena di nebbia fitta.

“Non è che abbiamo sbagliato nel buio, e siamo tornati indietro?” chiese Matteo dietro di noi.

Papà non sembrava per niente sicuro.

“Possibile?”

Craaaaa, craaaaa.

Il corvo stava davanti a noi, in aria, in mezzo al grigio nulla… ma non batteva più le ali. Come faceva restare in aria? Papà ci fece avvicinare. Piano piano vedemmo che il corvo era posato sopra qualcosa… ma che cos’era non si vedeva per la nebbia. Piano piano, con passo felpato, io e Pietro ci avvicinammo. Ora il corvo si vedeva muovere… con un salto e due battiti di ali si spostò più in alto… ripeté il gesto una volta, poi un’altra… si stava arrampicando… in alto… verso una macchia di nebbia luminosa molto in alto. Non poteva essere altro che il sole… Becherta andava sempre più in alto, posandosi dopo ogni salto su… su che cosa?

Ci avvicinammo, fino a capire che era un… albero! Un albero lì, nella viuzza! Ma non un alberello sottile, come si piantano a maggio ai crocevia con tanto di musica e balli. Questo era un tasso… come dire, vasto. Ed era vecchio, anzi, era proprio antico. Spuntava dalla terra con un tronco larghissimo, non tondo e liscio ma tutto a nodi e a costole, e anche spazi vuoti, come se fossero più tronchi diventati uno. Si alzava verso il cielo con rami curvi, intrecciati, ognuno spesso quanto un uomo cresciuto.

Aspetta… ma… la viuzza… non era stretta? Come poteva starci dentro un albero così enorme?

Ecco, quasi non c’eravamo accorti, ma in quella nebbia magica i muri dei palazzi non erano scomparsi soltanto dalla vista: erano proprio scomparsi del tutto. Voglio dire, completamente! Non c’erano più. Neanche un mattone. I palazzi erano scomparsi. La città non c’era più. In tutta quella nebbia c’eravamo solo noi, l’albero e Becherta.

Papà sospirò profondamente. Sapevo a cosa stava pensando: il corvo era tanto, ma tanto in alto.

“Niente,” disse lui, “mi sa che dobbiamo seguirlo… fin lassù…”

Per primo andava arrampicandosi mio papà, gli occhi chiusi stretti, sudore freddo sulla fronte e la faccia sbiancata per le vertigini. Poi seguivamo noi ragazzi, e poi Matteo seguiva più in basso, guardando su per vedere dove andava mio papà, e dicendogli come mettere mani e piedi.

“Forza, Faramundo,” diceva, “un po’ a destra… stendi il braccio di più… si, va bene, prendi quel ramo. Ora alza il piede sinistro…” e avanti così.

Che bel disegno che saremmo stati! Tutti ad arrampicarsi verso il sole, seguendo un uomo con gli occhi chiusi, sull’albero più grande del mondo.

A proposito, vi ricordate che ogni ramo dell’albero era spesso come il torso d’un uomo cresciuto? Ecco, per una strana magia quando toccava a noi più piccoli salire per gli stessi rami, erano grossi soltanto quanto i nostri corpi. E come se non bastasse, i rami che prima sembravano tanto lontani l’uno dall’altro, ora erano abbastanza vicini perché un ragazzo potesse raggiungere sempre il prossimo appiglio per arrampicarsi. Visto? Il Ghastengarda è così.

Quando papà raggiunse il ramo, altissimamente in alto, dove Becherta si era fermato, dalla nebbia attorno si sentì quella voce chiara e squillante che oramai conoscevamo.

La nebbia avvolge le verdi foglie

I rami, il tronco, la terra stessa

Densa e bianca, soffice accoglie,

Di un sole nascosto luce riflessa.

Figli di scultori,

E padri lor tutori,

Allungate la mano

Afferrate quel bagliore lontano!

“Quis!” disse papà. “Vuole che noi afferriamo… ho capito bene, ragazzi, vuole che afferriamo il sole?”

“Non è possibile!” disse Pietro. Fui fiero di lui, qualche tempo prima sarebbe rimasto zitto per paura di dire la cosa sbagliata. Si stava sciogliendo un po’, nella nostra compagnia.

“Afferrarlo? Non si vede nemmeno!” dissi io per sostenere Pietro. “Ci credo solo se lo vedo.”

Per la grande sorpresa di noi ragazzi, mio padre e Matteo risposero con le stesse parole allo stesso tempo:

“Se credi soltanto a quello che vedi, vedrai soltanto quello in cui credi.”

Furono sorpresi anche loro. Papà addirittura aprì gli occhi e guardo in giù verso il cugino, poi li chiuse di nuovo in fretta, barcollando sul ramo.

“Me lo diceva sempre il nonno,” disse papà, intendendo suo nonno, mio bisnonno.

“Non l’ho mai conosciuto,” Matteo rise, “lo diceva sempre mio papà.”

Mio padre sorrise, con aria nostalgica. “Lo zio Ricciardo… Va bene,” disse papà, “è sempre così: quando Quis mi chiede l’impossibile, chiudo gli occhi e penso al vecchio nonno, e ci provo.”

Allungò la mano destra più in alto possibile, verso il cuore luminoso della macchia dorata di nebbia sopra di noi.

“Sento qualcosa…”

Lasciò la presa sull’albero con l’altra mano, e si sporse completamente dal ramo. Con un grugnito per lo sforzo, si tirò su di peso e… scomparve nella nebbia. Per fortuna non caddi giù per la sorpresa, com’era successo la mia prima volta nel Ghastengarda.

“Forza, Faro e Pietro,” disse Matteo dal suo ramo più in basso, “anche voi adesso.”

Ci arrampicammo fin sul ramo dove Becherta stava, posato e tranquillo a guardarci, e anche noi allungammo la mano verso il sole nascosto. Sentii qualcosa di duro, rigido e fermo, dal tocco simile ai rami dello stesso albero. L’afferrai anche con l’altra mano, e mi tirai su…

…e mi ritrovai appeso a un ramo di albero. Un altro albero di tasso, più piccolo, più normale, e non più nella nebbia, ma al sole. O meglio, la luce del sole che attraversa le foglie di un bosco, tutta screziata e verdastra. Perché questo albero non era solitario, ma parte di una grande foresta. Mi sistemai comodo sul ramo, e mi guardai attorno. Papà stava più fermo possibile, occhi sempre chiusi, su un altro ramo vicino. Pietro era al mio fianco sullo stesso ramo. Sentimmo un fruscio di foglie sotto: era apparso pure Matteo.

“Siamo tutti qui?” fece papà.

“Tutti” disse Matteo.

“Benissimo, questo è il mondo del racconto. Ma dov’è Quis? Guardate in giro, voi che potete.”

Subito, giunse la voce di Quis da sotto.

Ecco, quaggiù mi trovate

Se lo sguardo abbassate.

E infatti il ragazzo dal viso angelico stava seduto su una radice sporgente dal terreno?? del nostro albero.

“Scendiamo da te, buon Quis?” chiese papà.

Venite, arriva una mia conoscente,

Che pronuncia la sorte di ogni nascente.

Il tempo preme, conosceremo insieme

L’eroe e il seme del racconto e della speme.

“Va bene, Quis” disse papà. “Soltanto che, io ci metterò un po’ di tempo, sai com’è. Ragazzi, mi aiutate voi a scendere?”

Con tanto di “un po’ più a destra, papà” e “un po’ più giù,” e “abbassa la gamba destra” e “no, no, un po’ su a sinistra” riuscimmo pian piano ad aiutarlo a scendere dall’albero. Toccando il suolo, mi accorsi per la prima volta che la terra sotto l’albero non era piana, ma in pendenza… eravamo in montagna! E ciò significava che non eravamo certo vicino a Pavia, circondata com’è da una vasta pianura. Ma che meraviglia! Fino a quel momento avevo dato per scontato che la magia del Ghastengarda era comunque confinata alla mia città…

Quis ci osservava sorridente e forse un poco impaziente.

Nell’attesa distesa della vostra discesa,

è salita spedita la persona avvertita.

E di fatto una giovane donna stava salendo tra gli alberi e piccoli cespugli, un copricapo di stoffa bianca in testa. Sul sentiero appena sotto di noi, si fermò, guardò Quis, a cui fece/che le fece un piccolo cenno rispettoso con la testa, come per dargli il benvenuto. Capii che i due si conoscevano già. Poi, senza dire parola, la giovane donna proseguì sul sentiero, e Quis ci fece cenno di seguirla. Sempre un po’ a distanza e senza parlare, camminammo nelle orme della donna fino a quando il bosco si aprì in una piccola radura, rivelando un panorama che mi tolse il fiato. Sotto di noi si vedevano chiaramente una serie di grandi massi grigi, ciascuno grande come una capanna, e sotto ancora il fianco verde e spiovente della montagna che si stendeva fino al fondo nascosto di una profonda valle. Ma la cosa più sbalorditiva era vedere un’altra montagna direttamente davanti a noi: svettava maestosa al sole, tutta scintillante di neve e ghiaccio, una cosa mai vista per noi ragazzi delle città di pianura. Da Pavia, nelle giornate più limpide, si vedono i picchi delle Alpi in lontananza, ma fino ad allora mi ero soltanto immaginato cosa si potesse provare a essere in mezzo a simili giganti rocciosi. Pietro era rimasto di stucco come me, e perfino Matteo. E papà? Chissà quante cose splendide aveva visto dentro il Ghastengarda… eppure rimase a bocca aperta davanti a tale splendore. Quis era deliziato dalla nostra reazione.

Che gioia fare vedere a nuovi amici

Un mondo di meraviglie incantatrici!

La giovane donna stava andando… dove? Non l’avevo notato a prima vista, ma c’era un piccolo villaggio nascosto fra i massi grigi sotto la radura. Fumo saliva dai tetti di paglia di una manciata di casette costruite in pietra grezza con tanta cura da essere perfettamente tondi (i tetti?). Infatti, si confondevano con i massi, e sembravano propaggini della roccia viva della montagna stessa. Bambini vestiti di lino grezzo giocavano per terra con dei cani, e capretti salterellavano attorno a una pila di fieno. Una signora corse incontro alla giovane donna.

“Dama Bianca, ringrazio il cielo che sei qui. Presto, presto…”

“Tua sorella partorisce” disse la giovane. La signora sgranò gli occhi.

“Ma come fai a saper…? Oh. Ah, si. Certo.”

“Non stare lì sbalordita. Portami da lei.”

“Si, si, presto, di qua.”

Entrarono in una casa al confine tra il villaggio e il bosco. Una piccola folla si era creata attorno, tra bambini i paesani, che guardavano curiosi la Dama Bianca. Prima di entrare in casa, si tolse il copricapo. I suoi capelli erano bianchi. Non il bianco di un anziano… è difficile spiegare, erano di un bianco folto e rigoglioso, quasi lucevano. Ci fu un sussulto di stupore tra tutti.

La Dama Bianca era entrata da poco tempo quando uscì un uomo, sicuramente il padre del nascituro perché cominciò a dare ordini ai bambini attorno alla porta, dicendo: “La Dama porterà alla luce vostro fratello, non serve stare qui incantati. Tu puoi spaccare la legna, tu puoi fare il fuoco, tu puoi prendere acqua dal ruscello… tu puoi fare erba per i conigli, tu puoi prendere le uova… e tu, piccolo, puoi venire con me.”

I fratellini erano ben sei, tutti dai capelli rossicci e riccioluti, e tutti maschi! Mentre si davano da fare, ogni tanto si fermarono e guardarono verso casa, gli occhi grandi e tondi, quando si sentì la loro mamma gridare per il dolore.

“Papà,” sussurrai, “anche la mamma griderà così quando nascerà il fratellino?”

“Il fratellino o la sorellina…” mi corresse con un sorriso, “certo,” mi mise un braccio attorno alle spalle, “ma tranquillo, è normale. Se questa signora ha già sei figli, vedrai che non ci vorrà molto tempo.”

Detto fatto. Presto, le grida tacquero, e dopo un altro po’ la Dama Bianca emerse dalla porta della casa, asciugandosi le mani sul grembiule. Si sistemò i capelli, e rimise il copricapo. La folla di paesani si era riformata, ma questa volta a una discreta distanza: guardarono la Dama con profondo rispetto. Il padre si avvicinò, il figlioletto più piccolo a suo fianco con un cestino pieno di tortine in mano.

“Ma grazie, piccolo,” disse la Dama Bianca, abbassandosi con un sorriso. Non mi ero accorto prima, era davvero tanto bella. Strana, con i capelli bianchi e occhi color ghiaccio, ma bella. “Tu hai un nuovo fratello. Non sei più il bambino della famiglia, adesso sei uno dei grandi.”

Il piccolo fece una risatina felice, e le porse il cestino. Lei lo prese, e gli dette un bacino sulla guancia. Alzandosi, la Dama Bianca parlò con il padre.

“Anche tu hai sei fratelli maggiori, tutti maschi, non è vero?”

Il padre annuì, solenne.

“Allora,” disse lei, “non dubito più di quel che ho visto. Un giorno, tuo figlio nato oggi conoscerà la montagna meglio di chiunque altro, meglio ancora dei nostri camosci bianchi. Sarà un cacciatore famoso, un arciere senza pari. Sarà colui che colpirà con il suo arco il possente camoscio bianco, Corna d’Oro… e porterà nella Valle del Soča il suo tesoro.”

Il padre aveva incominciato a sorridere per la contentezza, sentendosi raccontare il prodigioso talento futuro del neonato. Ma queste ultime parole gli congelarono il sorriso sulle labbra, e tra la gente del villaggio ci fu dapprima un silenzio stupefatto, e poi un sussurro, un mormorio, “Corna d’Oro! Il tesoro di Corna d’Oro! Nessuno ha mai osato… Nessuno ha mai sperato…”