Il tesoro del fiume

Illustrazioni di Francesca Duo

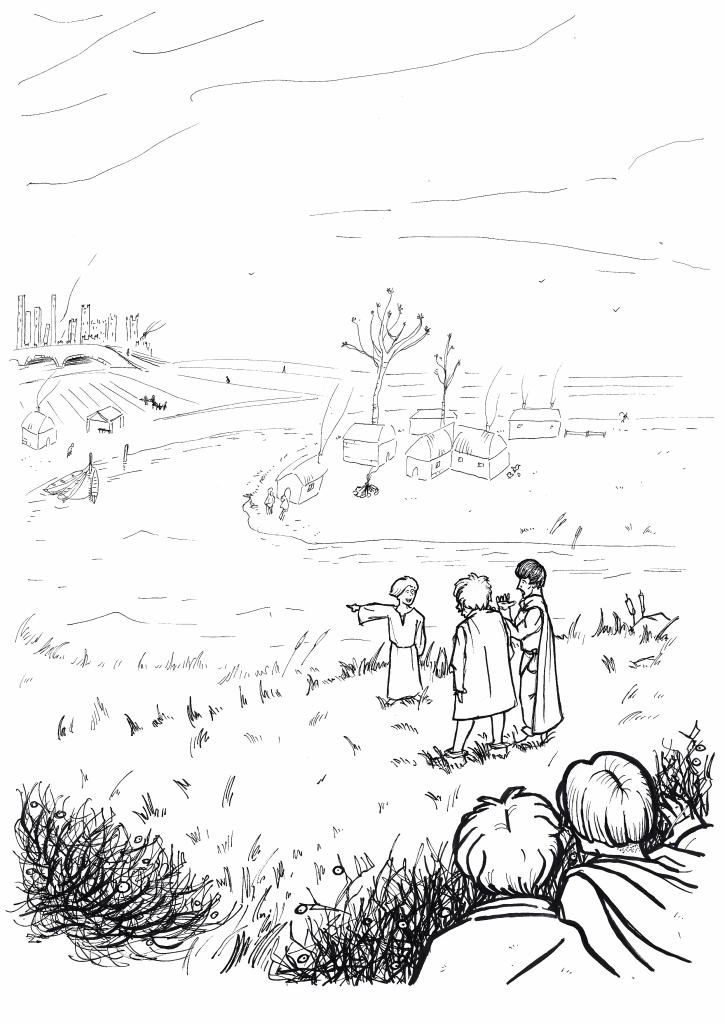

La terra era bella morbida. Per fortuna, perché siamo caduti proprio sul sedere, ma senza farci male. Che cosa? Sulla terra? Non dovevamo cadere dentro l’acqua? Ebbene, amici miei, eravamo dentro un mondo fatto di racconto: il Ghastengarda, l’aveva chiamato papà. Al suo interno, ogni magia era possibile. E ora ci trovavamo sull’erba bagnata e fredda, anzi, quasi ghiacciata, e attorno a noi la nebbia andava scomparendo. Nel giro di pochi respiri, infatti, si era alleggerita così tanto che riuscivamo a vedere tutto attorno a noi. Eravamo sopra una piccola altura, in mezzo a dei cespugli invernali senza foglie, e per fortuna i papà erano una ventina di piedi distanti, più in basso. Ci nascondemmo dietro quei cespugli a guardare. I nostri papà stavano parlando con…

…un ragazzino bello come un angelo, allegro come il sole. Era come se il figlio più bello e bravo del nobile più ricco della città avesse fatto cento bagni profumati, e si fosse messo vestiti lavati mille volte, e… e che ne so, non riesco a descrivere quanto era… pulito. E voglio dire, simpatico. Non potevi che volergli bene sin dal primo sguardo. Avremmo poi scoperto che il suo nome – piuttosto strano – era Quis.

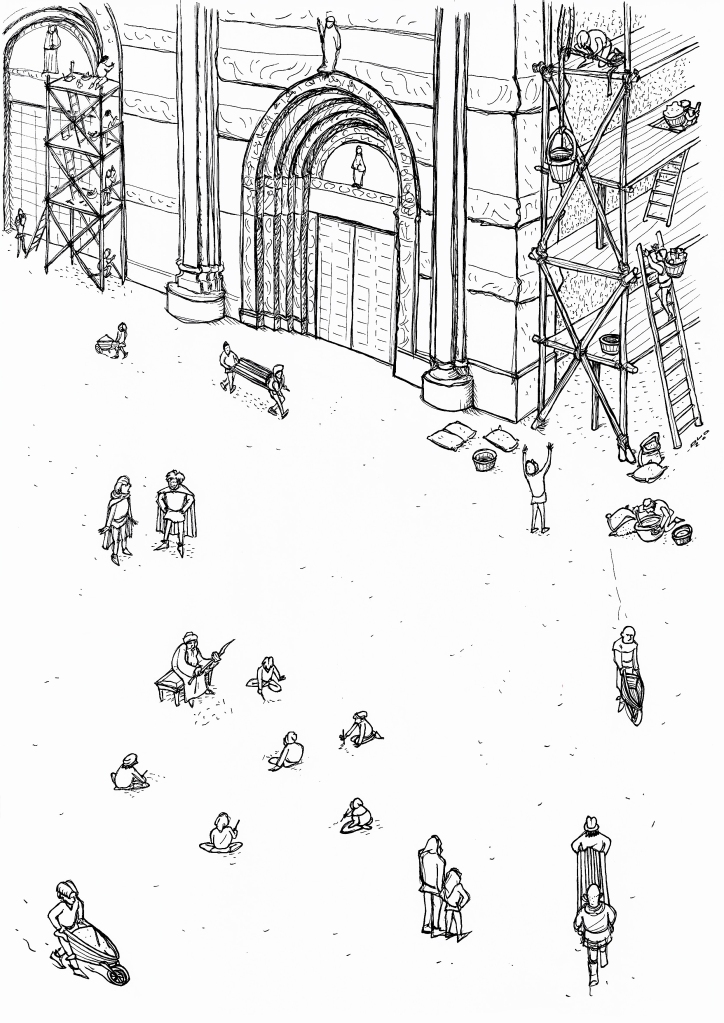

Ora parlava con loro. Matteo aveva una faccia meravigliata quanto le nostre, ma il mio papà sembrava completamente a suo agio – anzi, si stava un pochino divertendo per la sorpresa del cugino, secondo me. Il ragazzino angelico gli stava indicando qualcosa più lontano, in fondo in fondo, verso il fiume. Perché vedete, eravamo in alto sulle rive del Ticino, credo vicino a San Salvatore fuori le mura. A sinistra, in lontananza, riconobbi il ponte romano, e più vicino le baracche dei mattonieri e le barche dei pescatori.

…non ho mai visto un re sì avaro

Diceva il ragazzino.

Più del sangue, l’oro gli è caro.

Ha raccolto i beni della gente

Lasciandole poco o niente,

E ora che è fuggito dalla battaglia

Tutti vedono quanto è canaglia.

Ma a lui non importa, basta riempire

Le tasche di tesoro, e partire.

Ecco altre due cose incredibili di Quis: una è come parla. Sembra una filastrocca. Non so come fa, io ci ho provato e non riesco. Magari una prima rima mi viene in tempo, ma se poi vado avanti m’impappino e finisce lì. La seconda cosa è: quando sei dentro il Ghastengarda senti Quis dovunque sia, fa niente se sta a due piedi da te, o a mille. E mica grida, no no! Parla piano, e tu lo senti sempre.

Intanto, io e Pietro ci stavamo guardando e, vi ammetto, avevamo tanta paura. Ora eravamo stati trasportati da una strana magia fuori dalla città, e vi dirò di più, fuori dal tempo! Perché i mattonieri e i barcaioli laggiù sulle sponde del Ticino, erano tutti vestiti come la gente delle fiabe, come la gente nei dipinti più antichi nelle vecchie chiese della città, quelle crollate a metà nel grande terremoto d’anni fa. E la città, che un po’ vedevamo da lì, era diversa, più piccola, più legno e meno mattone, e non c’erano le torri. Lo dico ancora, avevamo paura.

Cosa fare? Uscire dai cespugli, farci vedere, e accettare una certa punizione, o restare lì nascosti aspettando di tornare nel nostro mondo e sperare ancora, in qualche modo, di farla franca? Voi che cosa avreste fatto?

Ecco che implora, blandisce, minaccia,

Ma il cuore dentro gli si ghiaccia.

Di nuovo Quis. Di chi stava parlando?

Ora vedemmo che i barcaioli parlavano con un signore alto e un po’ grasso, e mezzo calvo. Era vestito da povero, ma alle dita, che sembravano piccole salsicce, portava grossi anelli d’oro, con delle enormi gemme colorate, che certamente non riusciva più a togliersi. Sembrava muoversi con fatica, e sudava… eppure faceva veramente freddo.

“…ma dovete ubbidire, io sono il vostro re! Portatemi all’altra sponda, subito…”

“Ma vostra maestà…” diceva uno dei barcaioli, un giovane dall’aria timida. Un altro, più grande e più scaltro, lo interruppe rozzamente.

“Ma quale maestà, sciocco ragazzo? Io vedo solo un grasso arrogante in vecchi abiti strappati. Un re va in giro così?”

Quis era divertito:

Ahi ahi! Che brutta la testardaggine,

Un re travestito mi sa di asinaggine.

Sempre andavi, sospettoso, girando

Vestito da povero, la gente spiando,

Ma tutti lo sapevano, ci voleva poco fiuto.

Ora che stai cercando soltanto un aiuto

Ci provi ancora con lo stesso inganno?

Ma certo che non ti salveranno!

Ora sentimmo altre voci ancora, che urlavano: “È lui! È lui! Ariperto l’avaro! Ariperto il codardo! Nel nome del Signore, catturatelo!”

E dalla radura sotto le mura della città, arrivavano soldati dall’armatura stranissima, con scudi tondi, proprio come nei più antichi affreschi. Brandivano lunghe lance, ed erano infuriati. L’uomo dagli anelli d’oro si fece bianco come la calce viva, e cominciò a correre verso il grande fiume. Beh, correre… Dondolava, faticando come un’anatra sulla terra… Avete presente? Con tanto di lamenti e piagnucolii entrò nell’acqua gelida, mettendosi a guaire come un cagnolino.

I soldati, arrabbiati, arrivarono sulla riva quando lui era già nell’acqua profonda, e stava cercando di nuotare. Si fermarono: ovviamente, non valeva la pena di seguirlo, il suo destino era segnato. Quis scosse tristemente il capo.

Ma quale forza che trovi nella disperazione!

Non avevi mai fatto una corsa sì spedita,

Ma è l’oro che hai rubato dalla tua nazione

Che vuoi salvare ora, oppure la tua vita?

Ah! Le tasche son pesanti, e l’acqua è profonda,

Sbracci e sgambetti, m’arriverai all’altra sponda?

E infatti, proprio in mezzo al fiume, vedemmo che la corrente stava trascinando via l’uomo, che non ce la faceva più a stare a galla. Incredibilmente, ormai non tentava nemmeno più di nuotare, e teneva le braccia alzate fuori dall’acqua, stringendo nelle mani monete d’oro, rubini e zaffiri. Ben presto affondò.

I soldati stettero a guardare ancora qualche tempo, ma l’uomo non emerse più dalle acque.

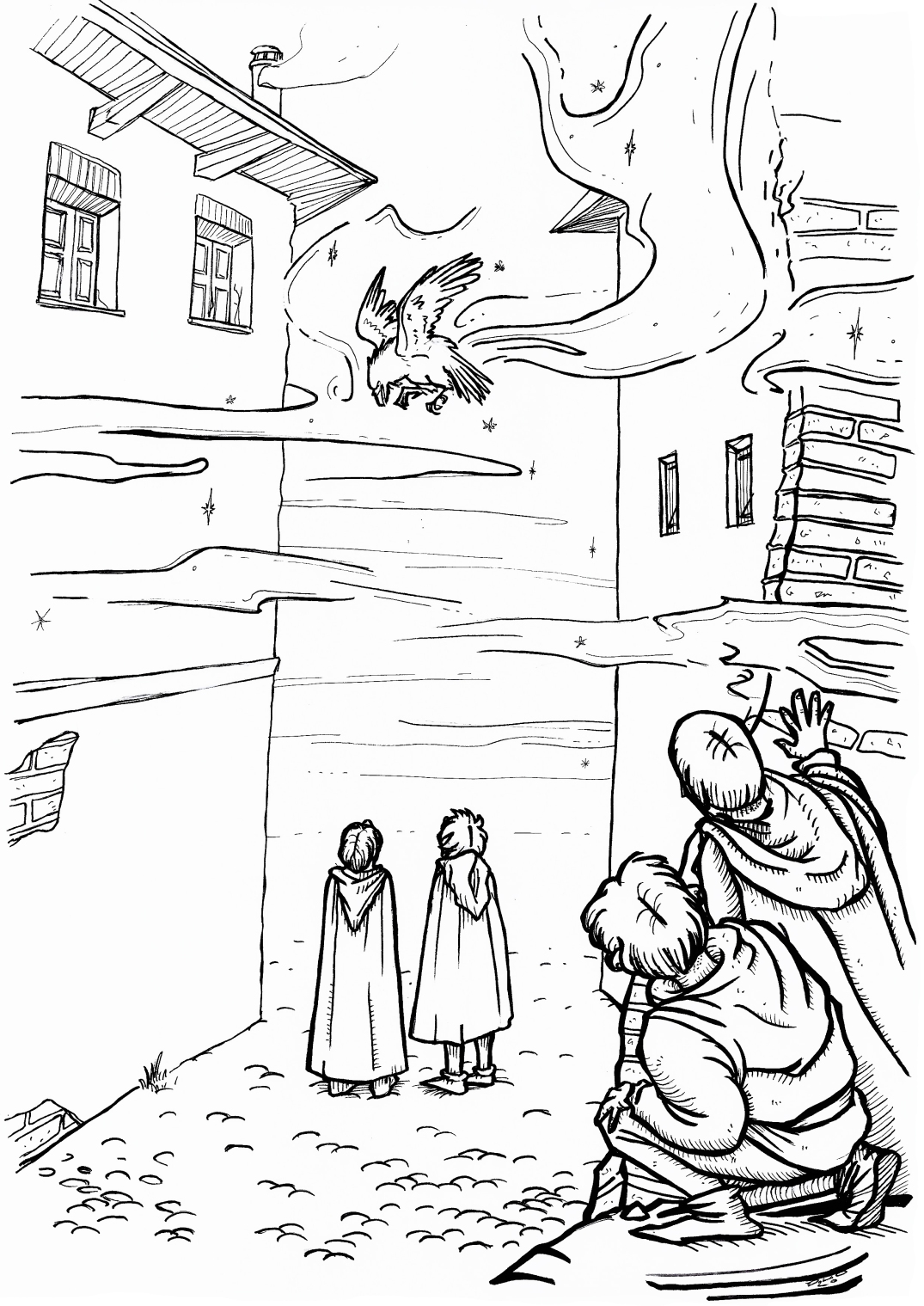

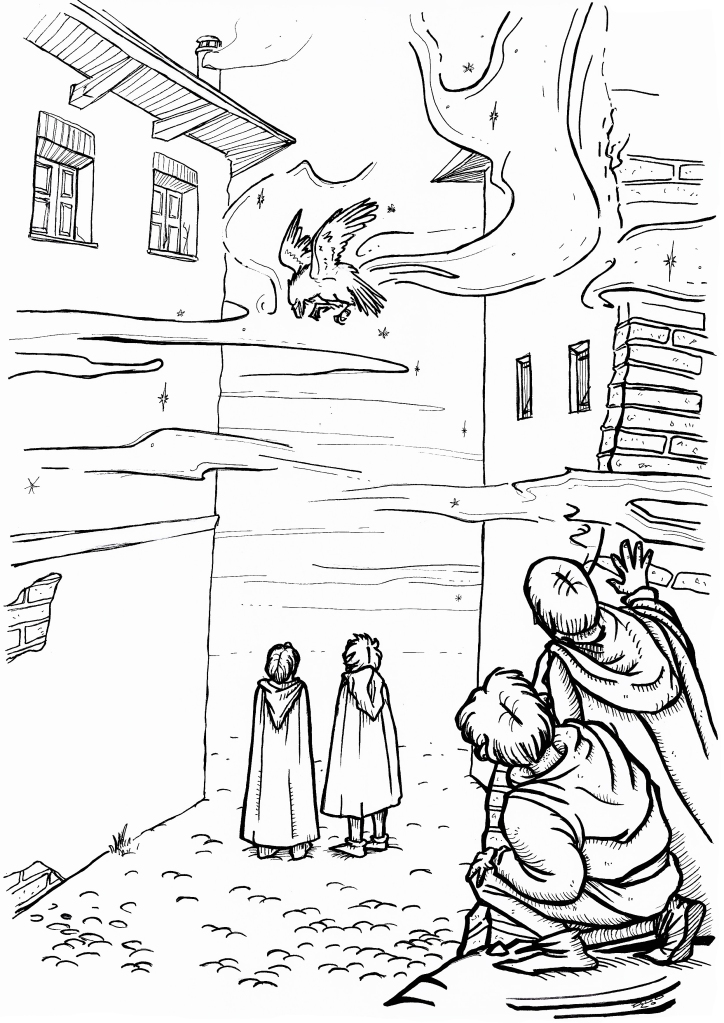

“Si è punito da solo” disse uno.

Proprio in quel momento, sentimmo il verso di un corvo, craaaa craaaa! Guardammo in su. Col pensiero tornai al corvo spargi-nebbia che avevamo visto nella viuzza di Pavia, ma poi vidi che questo corvo era più vecchio, con la testa quasi calva, e piume grigie sulle ali. Girava lento, proprio sopra le nostre teste, e gracchiò ancora…craaaa, craaaa! Quando abbassammo lo sguardo… non eravamo più presso il fiume.

“Il tesoro del fiume, il tesoro del fiume… Bah!”

Cosa? Di chi era questa voce? Dov’ero? Cos’era successo? Ma quanto mi sentivo disorientato! Non eravamo più sull’altura sopra il fiume. Io e Pietro ora ci trovammo sotto un vecchio noce, ed era primavera, perché le foglie erano piccole piccole, e d’un verde chiaro, le primissime dell’anno. Ma come? Cos’era successo? Non eravamo entrati in nessuna nebbia magica questa volta… semplicemente eravamo lì.

“Tuo padre vi ha preso in giro, te e tuo fratello credulone quanto te!”

Era la voce di una donna e veniva da una povera, piccola capanna di legno, tutta squadrata e pendente da un lato; il tetto sembrava che potesse cadere da un momento all’altro, e una stretta finestrella si apriva nella parete più vicino a noi. Fuori la finestra stavano i nostri genitori e Quis, intenti ad ascoltare la donna.

“Ma quale tesoro del fiume? Come ha potuto mio padre lasciare che io ti sposassi? Come ha potuto? Mi ha abbandonata qui, a questa vita misera, in mezzo a pesci puzzolenti… Per sempre!”

“Mia cara, non dire queste cose” giunse la voce di un uomo. “Mio padre di fatto non ha mentito. Ogni giorno portiamo al mercato un pezzo del tesoro di cui parlava…”

“Tesoro? Tu chiami tesoro un cesto di… di… minuscole alborelle?”

“Prima di lasciare questo mondo, mio padre ha fatto promettere a me, e a mio fratello di lavorare sodo ogni giorno con le reti a cercare il tesoro del fiume. E così ogni giorno portiamo al mercato sempre più pescato. Presto avremo abbastanza denaro per cambiare il tetto, e forse costruire un’altra stanza…”.

“Sei tu che non hai compreso un fico secco, marito! Ti do ancora una possibilità. Ma questa volta non lascio la mia sorte nelle tue mani. Vado dalla fattucchiera Edburga, ci deve un favore. Tornerò tra poco”.

E sentimmo sbattere una porta – in verità era più il suono di una porta che si rompeva – e una donna alta, altezzosa, dai capelli biondi e gli occhi scuri, si allontanava dalla capanna a grandi passi rabbiosi. I nostri padri e Quis la seguirono a una distanza discreta, per non farsi notare. Quis commentava, ridendo:

Ahi ahi! Che brutta la testardaggine,

Questa moglie ambiziosa mi sa di asinaggine.

Se dalla fattucchiera Edburga sta andando

Per chiedere un favore

In questo nero umore

La porterà soltanto allo sbando.

Ancora una volta Pietro ed io ci guardammo. Cosa fare? Seguirli?

“Andiamo” disse lui, “e facciamoci vedere da loro. Dai, Faro, ora basta. Arrendiamoci, i nostri papà ci daranno due sberle, e finirà lì. Non voglio smarrire la strada e rimanere per sempre in questo strano posto… tempo… mondo… non so bene che cosa”.

“No, dai, stiamo andando alla grande. Dobbiamo solo tenerli d’occhio. Prima o poi torneranno a casa, e quando succederà torneremo anche noi, senza farci vedere, come niente fosse”.

Pietro non era convinto, ma non gli diedi tempo per pensare.

“Forza Pietro, andiamo, se no li perdiamo di vista”.

Era vero, i due e Quis stavano per scomparire nel boschetto. Pietro mi lanciò uno sguardo incerto, ma si mise a camminare.

Quis aveva parlato di una fattucchiera Edburga. Chi era? Di lì a poco avremmo capito che si trattava di una donna estremamente anziana, che parlava strano e viveva in una casetta sotto un gigante, maestoso pioppo nero. Beh, casetta… dire così fa pensare a una casa fatta di legno, almeno. Ma al posto delle pareti e del tetto c’erano solo vecchissimi mantelli di lana appesi ai rami, uno accanto all’altro e cuciti insieme, e poi ricoperti di piume di uccelli d’ogni colore e forma. Una sorta di tenda piumata. Era la casa più strana che avessi mai visto. Ma senza dubbio era la casa giusta per una fattucchiera.

Edburga stava seduta per terra, e vestiva un vecchissimo mantello di lana ricoperto di piume. I suoi occhi erano bendati, e capii che era cieca. Aveva acceso un fuoco, e stava arrostendo qualcosa. Dal profumo sembrava pesce.

La moglie del pescatore le si avvicinò.

Giunti sul posto, Quis e i nostri genitori si mantennero nascosti, per non farsi accorgere e noi, doppiamente, ci nascondemmo alla moglie del pescatore e a loro.

“Edburga,” la moglie del pescatore non la salutò nemmeno, “quel pesce te l’hanno portato mio marito e suo fratello?”

La fattucchiera sorrise sotto la benda.

“Buongiorno”.

“Dico io, quel pesce te l’hanno portato mio marito e suo fratello?”

“Tutti i pescatori mi portano qualcosa di tanto in tanto. Tuo marito si chiama Picaldo, e suo fratello Pacoldo, vero? Ragazzi per bene”.

“Anche il padre di Picaldo lo faceva, vero?”

“Certamente, e anche suo nonno. Uomini saggi e generosi”.

“Allora tu ci devi… non so quante centinaia di pesci, da generazioni… Adesso basta. Dicono che sei una fattucchiera potente. Vediamo! Quando mi sono sposata, mio suocero ha promesso che Picaldo e Pacoldo avrebbero trovato un tesoro nel fiume. Invece ogni giorno portano a casa i pesci più piccoli che esso contiene, le alborelle, e niente tesoro. Io sono stufa. Fa che peschino d’ora in poi i grandi storioni fatati che hanno ingoiato il tesoro del Re Ariperto, come dicono i cantastorie!”

Dopo un lungo silenzio, la fattucchiera rispose:

“Sicura, mia cara? Le alborelle sono più gustose degli storioni, hai mai provato a farle in carpione?”

“Non mi prendere in giro! Voglio vivere come una donna normale, con una casa decente, e vestiti decenti. Fa come ti dico, e ti sarai sdebitata con noi di tutto il pesce che hai mangiato “.

“Allora, farò come chiedi. Ma dovrai darmi uno dei tuoi capelli”.

“Uno dei miei…? Ah, sì. Per la magia. Certo!” E con una smorfia di dolore, si strappò un lungo capello chiaro dalla testa. Lo porse alla fattucchiera, e vedemmo che le tremava un po’ la mano. Non era sicura di sé come sembrava.

La vecchietta ora fece qualcosa di veramente strano: tenne il capello tra due dita, ci soffiò sopra leggermente, per tutta la lunghezza e poi… lo lasciò cadere. E qui successe una cosa che mi fece venire i brividi… il capello cominciò a muoversi come… come un verme, e infilarsi sotto la terra. Giù, giù, e giù, fino a scomparire del tutto. Poi, con espressione determinata, la fattucchiera scavò con le mani, e presto tirò fuori dal suolo un grasso lombrico, lungo esattamente quanto il capello.

La moglie guardò il tutto con una faccia tanto affascinata quanto disgustata. La fattucchiera, calma e decisa, sussurrò qualcosa al verme, che smise di agitarsi, e si calmò. Dopo qualche attimo un pennuto, credo che fosse un tordo, venne fuori da un cespuglio vicino, si posò sulla mano della fattucchiera, prese in becco il lombrico, e volò via.

“È questa la tua magia, fattucchiera?” chiese la moglie del pescatore. Era chiaramente impressionata, ma delusa.

“Questa è la mia magia” annuì Edburga.

“Bene, arrivederci”.

E con questo la donna si allontanò più in fretta possibile.

Craaaa, craaaaaa!

Sentimmo di nuovo il verso del corvo dall’alto. Guardammo su a quelle ali nere e grigie… Battemmo le palpebre, e tutto d’un tratto non eravamo più alla casa della fattucchiera Edburga.